Extracted from a paper published in MAY 1982 – THE FACULTY OF HISTORY OF ART AND DESIGN, DEPARTMENT OF PRINTMAKING, DUBLIN

Introduction ….

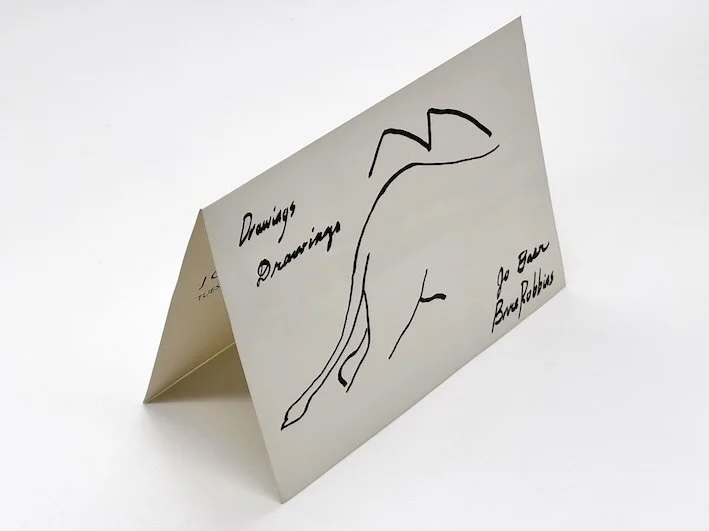

For the last four years, Baer has collaborated with British artist Bruce Robbins (they live and work in Ardee) on large canvases and a series of drawings using figurative imagery exclusively. The result is large (4ft by 5ft), delicate, and fragmented drawings which allude to primitive cave drawings more than anything else. The canvases are very large with an emphasis on the fragmentation of images, worked in heavy black and white, light and dark contrasts. Both artists have developed increasingly complex attitudes towards the representation of reality. They tend to reduce painting to a definite number of contingent parts, using in a premeditated way the devices of figurative painting. Therefore, they tend to use parts of objects in their work, in which anything will do….star charts, horses, whips, because essentially the subject matter is irrelevant. Like Baer’s earlier work, it is formal concerns once again that interest her. Figurative imagery is dealt with in abstract terms until it becomes abstracted itself. This distinguishes their work from a lot of the current figurative investigations being done by artists who tend to use imagery with a more identifiable social meaning.

The difference between these new collaborative pieces and Baer’s early work seems vast in terms of style and content. Upon initial viewing these pieces are so different that one is apt to question the continuity of Baer’s work in view of such an extreme change in style. Actually, some of the same concerns that interested Baer in previous pieces are dealt with by herself and Robbins in a different manner. For example, the tension created by the large areas of flat colour contrasted by the delicate, floating images in their drawings is not dissimilar to the tension created by the bands of colour on either side of a neutral area in the “Double-Bar” paintings. Each image can be viewed in isolation from the rest of the piece or as a whole. Baer also approaches these new collaborations with the same objectivity and emphasis on materiality that her earlier work developed from. These works continue to embody a search for purity in form and structure. Baer and Robbins are just beginning to produce pieces which they are pleased with — both are perfectionists, Baer particularly has the habit of destroying work until she is satisfied.

The figurative format they have adopted has some adjustment. This thesis coincides with the first public showing of their drawings and paintings at the Lisson gallery in London. They have been working in collaboration on these pieces for the last four years, but up until now, they have been having problems persuading any gallery to exhibit the work. The older, more established dealers in New York have been unable to deal with the change in Baer’s style, and the newer galleries are only now coming round to showing the work, most probably because of the similarities to the current “post-modernist figurative” trend in painting. These new pieces represent Baer’s willingness to move from the more formal rhetoric of the previous Minimal paintings to new variations of figurative representation.

CHAPTER III: BAER, ROBBINS, AND THE NEW FIGURATIVE PAINTERS

‘It is true we inherit a pictorial convention, but painting has challenged and reduced this inheritance, decade by decade, so that pictorial allusion inheres no more now in paint than in wallpaper.1 Some recent paintings exist that are not pictures.’ 1

‘On this occasion there is a concentration of work which has something to do with painting, some of it frankly antagonistic to that whole tradition, but most displaying a more complex ambivalence to its value, choosing to masquerade as painting in order to address the problem at its very centre.’ 2

The above quotations relate to the changing face of painting in these times, which has resulted in a myriad of different styles and approaches using the same media. By emphasizing the objectives behind dominant movements within painting, these quotations also illustrate chronologically the evolution of ideas in relation to painting during the last twenty-five years. The second quotation – from Thomas Lawson – outlines the attitudes of some recent figurative painters surfacing in New York – artists interested in working with figurative imagery in a “new” way and intent on returning a social content to their work. Baer and Robbins’ recent collaborations have been done with some aspects of this work in mind. The first quotation – from Jo Baer – stresses the “Minimalist” conception of painting as a conveyor of pure ideas. This pursuit of ideas within painting resulted in all traces of pictorial allusion being stripped away, enabling paintings to exist not so much as “pictures” but as autonomous forms alluding to nothing but themselves herein lies one of the problems central to Minimal theory and to a lot of the painting done under the guise of Modernism. Towards the end of what could be termed as Minimalism, there seemed to be little real connection between what was going on in the art world and what was going on elsewhere. Minimalism became caught up in a narcissistic system, self-regarding, self-enclosed, and consequently powerless. Contrary to Baer’s point that “some paintings exist that are not pictures”, it is impossible for a painting to exist separately from the history of the medium, as historicity is inherent in the very nature of painting. Paintings, therefore, are always viewed as “pictures” in some sense as long as they adopt the format of painting. Even Baer’s Minimal paintings are historical as they are contained within a rectangle and worked with oil paint (an artistic convention). If we look at art history, we see that most movements have a beginning and an end, and no piece of art can be viewed outside history. In the case of Minimal painting problems became more and more self-referential until artists were to find themselves confined within their own limiting dictums which led to a deceleration in the power of the work. This is not to say that Baer’s investigations were not necessary and powerful at some time (they were), but simply because of the nature of the work, such an objective approach was bound to become entrapped within its own ideological construction. Baer realised this and has since moved on to other problems within painting. A younger generation of artists also realised this and have been working on paintings which have rejected the precepts surrounding most Minimal and Conceptual works of art.

Like the “New Image” painters, Baer’s most recent collaborations with Bruce Robbins have resulted in pieces primarily concerned with re-observing and re-using elements of figurative representation. By fragmenting depictions of various objects into a collection of dependent parts and reassembling them as a whole, Baer and Robbins use figurative representation as a device for more formal concerns, i.e. “the possibility of integrating figurative imagery in space without it becoming illustrative”. 3 The reasons behind this seemingly extreme “change” in direction embodied in these most recent paintings can be attributed to several specific points, notably — The influence of the “New Image” or “Post-modern” painters, a group of younger artists who have evolved from and re jected the ideas of Conceptual and Minimal art and see the return to the use of figurative representation in a “new” way as a possible way forward. Baer and Robbins identify with this group in some respects. Baer’s collaboration with Bruce Robbins. Her move away from the mainstream in New York to the relative isolation of Ireland. To understand the intentions behind Baer and Robbins’s pieces it is necessary to look at their work with each of these points in mind. Firstly, one might compare Baer and Robbins’s collaborations with the recent figurative investigations being done by the “New Image” painters, as there are definite similarities as well as definite differences between the two.

By the sixties and seventies, the power of movements within Fine Art culture was becoming increasingly evident with the increased patronisation of artists by critics and galleries. Under this system, art had become another saleable, marketable commodity with New York emerging as the leading centre of such activity. This also resulted in an artificial sort of situation where it could be argued that movements have had more of an influence on artists than real life. As Ingrid Sischly of Artforum said: “The difference between generations of artists is now one year, one season, one cycle”. Set against this background, a new generation of artists began to emerge. They had evolved from a point of view shaped by the knowledge of Conceptual and Minimal art, the photographic image, and mass culture. Unwilling to act as an extension of the “Art Machine” 5, these artists began working figuratively with found imagery. The result has been that the work itself becomes a process of recycling — it is both “old” and “new” in content. To use “New Image” as a label to describe this type of work seems contradictory because the work represents an approach to the image as old. Artists like Baer and Robbins, Niel Jenny and Thomas Lawson use paint, recognizable imagery and canvas in a most conventional and unconventional manner. The “New Image” painters claim that newness is now a matter of recycling:- Without the spirit of escape or transcendence which the new represents, there is only the predictability of the cultural cycle, of image turnover. The new approach to the image is new because it is without the lustre of newness. It reflects the eye of the consumer who has seen these images before. The result has been the conscious production of rather awkward-looking, heavily painted canvases that use the ever-present images of consumerism and the media as their subject matter. At first sight, the paintings seem like rather inconsequential, amateurish attempts at figurative representation, but their executors claim they are much more than that. By using the devices of figurative representation in a consciously primitive manner, these artists claim that they address the problem of painting and the media image at its very centre by throwing the meaning of such images into confusion. These paintings are not celebrations of a return to a conventional oil and canvas format but, rather, antagonistic statements against that tradition, heralding perhaps the end of painting if anything by choosing to “masquerade” as paintings.

By the late seventies, the New York galleries had shown a variety of regional forms of figurative representation: one year the Italian figurative painters like Francesco Clemente, the next the German Expressionists, and most recently the “New Image” artists from New York. It is rather confusing and difficult to separate these different manifestations of figurative concerns because of the newness of the work and because, at first glance, many of the works by the Europeans seem quite similar to many of the works done by the New York artists. Nonetheless, the Americans have emphasised their differences and view their pieces as a counter-tendency against the European Expressionists mainly because of their concentration on the mediated, recycled, and social aspects of the imagery.

To draw a comparison — Francesco Clemente’s paintings have evolved – from the style of traditional Italian painting to a very simple, expressive manner of drawing. His work is figurative, erotic, and sometimes grotesque in content. Nude figures are presented as isolated, alienated individuals; the work is essentially allegorical in nature. The quirky, rather eccentric canvases of Thomas Lawson are paintings of appropriated imagery. Lawson does not invent images; he confiscates them. He lays claim to the culturally significant and poses as its interpreter, making the image become something else by adding another meaning: … the result is only to make the pictures all the more picture-like, to fix forever in an elegant object our distance from the history that produced these pictures. This distance is all these pictures signify. Clemente’s work seems to concentrate on two things – images, sometimes erotic, other times frightening and grotesque, light pastel colours with figures suspended within pure colour. Lawson’s work is more objective and has a less personal quality. Like the media he recycles, he is neutral, merely allowing what is already there to show itself as alienating — the images that surround our everyday lives. While Clemente’s paintings always lead us back to the individual visions of a well-constituted artist’s ego, Lawson’s paintings deny personal references and question the very root of our cultural formation.

The collaborations of Baer and Robbins lie somewhere between these two approaches.

CHAPTER IV: BAER AND ROBBINS (1977 -) I:

Collaborative Work At the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, England, from October through to November 1977, Baer exhibited a retrospective collection of works, including pieces from her Minimal period through to the “Wraparound” and “Double Bar” series. It was in Oxford, while working on the exhibition, that she met Bruce Robbins, a young British artist who up to that time had been working in a Conceptual vein on problems concerning image and language. The textual and photographic elements in Robbins’s works are most apparent between 1975 – 1977. These works present theoretical and ideological problems by paring down visual imagery to pure language. There is a great similarity between these pieces and the precise “Double Bar” canvases of Jo Baer, done roughly around the same time. Both concentrate on specific formal problems – Robbins’s works result in a rather complicated conceptual-linguistic style. Before these pieces, Robbins’s works used a variety of different media – photography, drawing, text, in an installation format. Rather than concentrating on individual pieces, Robbins created whole environments, his work never being strictly media-determined.

In 1977, the year Robbins first met Jo Baer, he had already begun to paint figuratively with oil and canvas. Both artists -36- met at a time when the direction of their respective works was undergoing a transition. For Baer, the retrospective exhibition represented the completion of a series of works and the end of a particular set of ideas. The “Wraparound” canvases had indicated that she was moving away from the strictly Minimal format but the direction that her new work was to take was still somewhat unclear. Her subsequent discussions with Robbins in Oxford clarified a lot of ideas that she had been considering in relation to the possibility of a new approach to figurative representation. She and Robbins began to realise that their intentions were quite similar. Both had evolved from a point of view shaped by the objective quality of Conceptual and Minimal ar, both had a substantial body of work behind them, both wanted to use figurative imagery and both felt that the possibilities of their previous works had reached an impasse of sorts. After their meeting in Oxford, they began to collaborate. This collaboration to the present has resulted in several canvases and numerous large drawings in a figurative style. Unlike Baer, Bruce Robbins had dealt more extensively with figurative imagery in past works so that the new format these drawings were to adopt was not completely unfamiliar to him – he had always used conventional drawing in most of his installation pieces. Initially, the combination of the two different styles within one work seemed to work very well, and although the line and composition of each artist was different, both seemed to merge perfectly. After many experiments, both artists realised that it was primarily space they were dealing with – the relation between line and space, the tension and intensity it created, figures in space, content and space, etc. One particularly interesting point which arises is the continuity of such a “change” in style. Due to the extremely objective nature of dominant movements in contemporary American art, works began to lack all humanistic impulse and all traces of personality. For this reason, the change in “style” by Baer and Robbins does not seem so unusual or contradictory. By approaching pieces as problems in objective formalism to be solved in an almost systematic manner and by eliminating all personal references in relation to subject matter, the artists become neutral, merely allowing the work to reflect specific formal concerns or cultural formations. Under this system, it is difficult to term changes in style by Baer and Robbins as contradictory. It seems that for many contemporary artists, seeing the imprint of popular culture in the self means taking a distanced vantage point from oneself. Artists began to see themselves as culturally formed entities subject to the changes within culture, and it seems that Baer has always regarded her work in this manner – Art which mirrors the present moves in a different way ,from another cause and toward another effect. Its mainstream is the status quo. It is unidealized, displaying both the good and bad aspects of now. The “New Image” artists take an even more distanced and objective viewpoint, as they see themselves as totally reliant on popular culture for their imagery. This is a new kind of objectivity grounded in the collective subjectivity of popular culture. It is quite obvious how such an attitude developed from the “impersonal” styles of Conceptual art and Minimalism. The importance of a “personal” artistic vision has seemed less and less important to artists in recent years. The artistic ego disappears almost completely amidst a rapid succession of “movements” and image turnover. The “New Image” artists question cultural myths by using them in their paintings. This work takes its cue from the observation that all cultural production is necessarily fictive and looks hard and long at the ideological myths embedded in that structure. These paintings use recognisable imagery, imagery with identifiable social meanings, but reproduce them from memory or photographs so as to throw these meanings into confusion. So, this imagery, appropriated from popular culture, becomes an important source of mythology and symbolism for an unusual, allegorical type art. Images taken from the media are presented in a different manner, within a different “aestheticised” context, so as to question their significance. The appropriated image may be a film still, a photograph, a drawing, or it may be a reproduction. However, the manipulation to which these artists subject such images works to empty them of their resonance, their significance, and their authoritative claim to meaning. Baer and Robbins have done something similar by reducing figurative representation to its simplest form, pure line, and fragmenting the imagery into a number of contingent parts.

By the shearing away layer upon layer of detail until representations are mere lines, enlarged and fragmented, the drawings become resolutely opaque. The floating, somewhat empty, images seem to represent their desire to capture the transitory, the ephemeral in a fixed image. For this reason, the images become something more than figurative representations. The eye can envision the drawings in two ways: (1) as allegorical, figurative imagery represented as petrified, static landscapes; (2) as purely formal, imagery which transcends its own meaning, becoming pure form, fragments of images, and lines which are interrelated and intertwined when viewed as a “whole”. Although Baer and Robbins draw analogies between their work and the work of the “New Image” painters, there are some distinct differences. The points these works have in common are they they both utilise appropriated or found images and both have an allegorical content. Still, the found images of Baer and Robbins are objects that surround them rather than subjects with an overt social significance. Unlike the “New Image” painters, Baer and Robbins seem to work from a less politicised point of view and seem more concerned with specific formal problems within painting than with presenting works as “aestheticised diagrams of cultural landscapes”. 4 Contrary to the consciously murky, rather eccentric canvases of the “New Image” painters, Baer and Robbins’s pieces are very precise, well executed and carefully presented. They seem to tread the thin line between producing works that are merely delicate, beautiful line drawings and works that solve definite problems and make definite statements. The static, rather displaced feeling of the fragmented images is what makes these works interesting. Baer and Robbins’s first exhibition of collaborative drawings is the result of four years’ work and consists of roughly eight paintings and twelve drawings. The canvases use oils and the drawings are conte and crayon on paper. Upon initial viewing, the arrangement of the exhibition has the quality of an installation because of the placement of the black and white drawings within a large white gallery space. The eye tends to regard the delicate black lines of the drawings as isolated in a huge void of white, which creates a sort of floating sensation between the lines, which seem to 1lie suspended in real space. The drawings are attached directly onto the walls without frames. The tension between the lines of the drawings and the white walls of the gallery seems to activate the space surrounding the works. Baer says that the choice of her/Robbins’s subject matter is of little importance and that they specifically use objects that they find around them — their own bodies, whips, chairs, star charts… anything available. Like the “New Image” painters, the material is usually drawn from memory. The paintings particularly seem to present stories; there is a suggestion of fantasy, a whiff of allegory, but because of the fragmentation of the imagery, it is difficult to read a deliberate story into them, for they lack sufficient clues or are overloaded with too many of them. Because the imagery is fragmented and suspended all over the canvas, it lacks definite beginnings and ends. The pursuit of naive or archetypal forms seems apparent in these paintings. Like the European Expressionists, the paintings have a detached, ritualistic feeling and a strange sort of erotic quality. Paradoxically, the eroticism of the imagery (the drawings illustrate parts of the male and female form- arms, breasts, buttocks…) is not dynamic but rather static, impotent, repetitive. Because of the use of identifiable objects the paintings suggest meaning but then defy meaning because of the allusiveness of the imagery. This as well as the fragmentation of the drawings gives them the quality of primitive cave paintings that must be deciphered rather than read. It is difficult to talk about individual works because none of the pieces are labelled, but one disconcerting quality of the exhibition is the inclusion of several additional canvases in a separate part of the gallery, one floor below the rest of the exhibition. This seems to break the continuity of the drawings and paintings on the main floor as one tends to view the main part of the show as a whole because of the way the pieces depend and relate to one another and the space around them.

…

The above is an extract from a longer essay. This selection relates specifically to the works on this website in the series ‘Sired in 82’. The title of that section is derived from the thoroughbred stallion listing of 1982, each drawing in this series was named after one of the stallions listed in the book, with the exception of “Brigadier -” and “- Gerard” where both drawings were intended to be shown as a diptych. BR

Leave a comment